The Green Myth: Proposals for an interspecies future

Introduction

My thesis studio practice and subsequent research uses biodiverse portraiture to respond to the anxious future of Earthly biology. I work with the belief that all future sexual politics and liberation is predicated on humanity’s relationship to natural resources; adopting the hypothesis that given the contemporary state of the ecosystem these various fields of activism will eventually be interwoven. The subjects of my oil paintings, semi-anthropocentric, synthesize not different political ideologies but different species entirely. This drive to create and investigate the future of biodiversity on Earth came from an overwhelming feeling of doom and a general fear of the future. In May of 2019 I suffered a breakdown. Popular news sources had theorized the Apocalyptic date in 2050 where the world would basically die off, and there existed a general attitude that nothing could be helped. My hesitation and general anxiety about the state of the ecosystem moved from passive to completely manic. I stopped eating, speaking, going outside, or leaving my bed. My outlook on life had been cut down at the knees, and almost irrationally I dug through literature that would help me feel anything. This research and artistic endeavor provides utopian answers for myself as well as others sharing similar anxieties about the future.

Eventually my artistic practice became therapeutic. My psychological outlook was informed by the innovative drive of all other living organisms on Earth. Faced with extinction, various animal species radically evolve their social and biological structure to adapt to the surroundings. Genetic chains that fortify finality and homogeneity leave animals to reproduce sans mutation; the harmful results of inbreeding and genepool shrinkage can be seen in European royal history.

When I heard ecoactivists refer to the Anthropocene, I thought a lot about whales. 50 million years ago, the whale was a quadruped creature living on the land. Facing rising ocean levels and more abundance of food in shallow water, the whale became amphibian and eventually entirely marine; front legs becoming flat fins and hind legs collapsing into the abdomen. Contemporary humpback whales still have the skeletal remains of hindlegs. These genetic fossils testify to the radical reproductive evolution of the natural world. It proved to me, on a personal level, that nature would always survive.

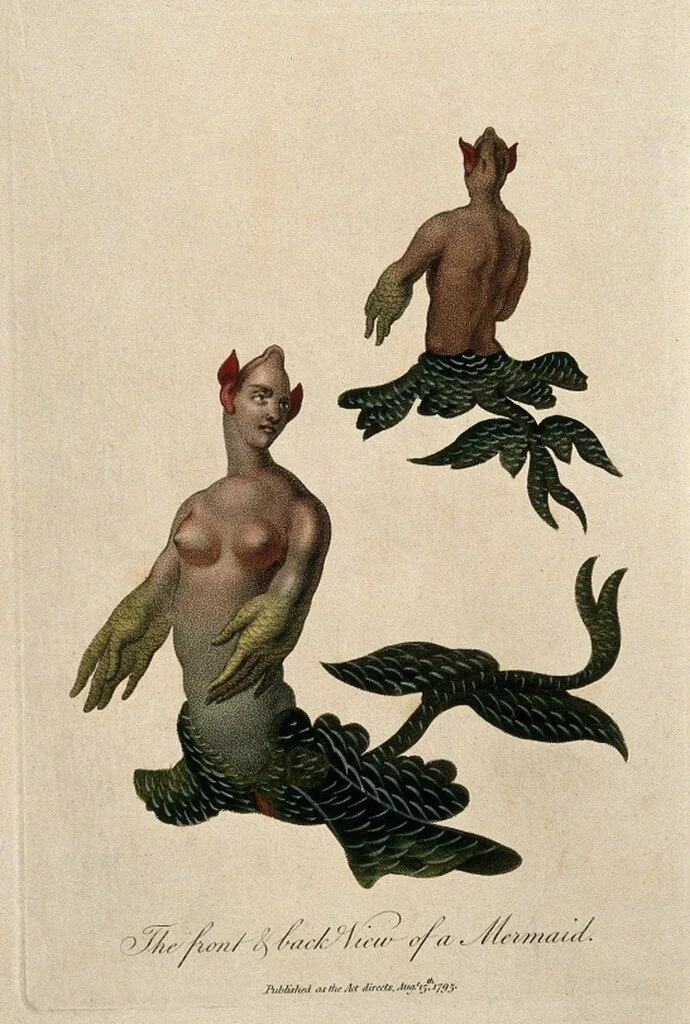

Looking at the history of both natural science and oil painting, it became clear that the archetype of the adapting beast was always present. Not only evolving independently, the hybrid body actually attracted the human gaze for its genetic potentiality. Programed to reproduce infinitely, it seems only natural that sexuality would eventually fantasize the posthuman. Artists throughout history depicted the sexual siren calling out to a passing sailor, or the muscular centaur fighting enemy armies. Oil painting, in particular, became my medium of choice because of its historical saturation with the mythological figure. Thus, the whale with hind legs is a manifestation of the rejection of doom and the introduction of invention. My personal relationship to hybridism became both scientific and spiritual; somewhere between Darwinism and witchcraft. I knew my painting practice and medium mixing could be scientific, while my subject matter could be mythical. The future of biodiversity on Earth will need all forms of expression and innovation.

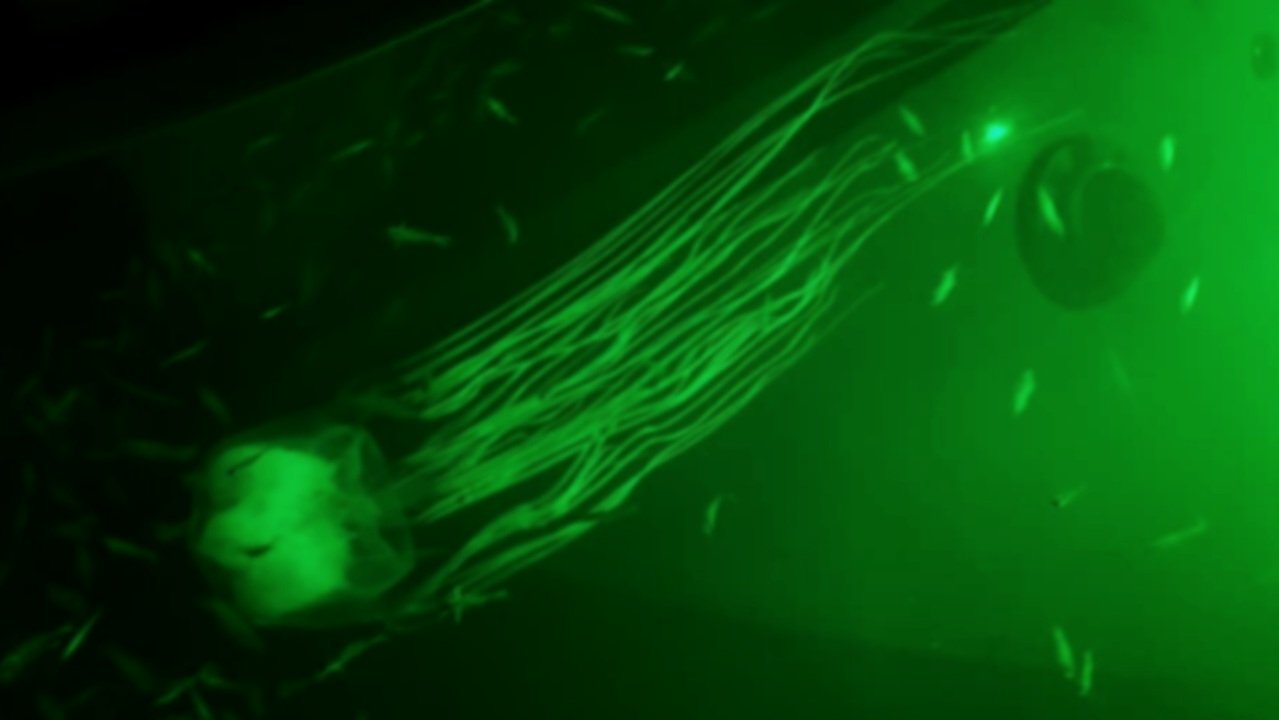

In the fall of 2019 I found a certain color paint that I wanted for the walls of my studio. It was a pale, glowing green and was available to be mixed entirely non-toxic at the Brooklyn hardware store where I picked it up. Painting my studio, something about it changed the entire space. It was green in the normative sense that it was eco friendly. Also, this green would indicate to the passing visitor that I had an interest in nature and plants in my research. That said, this green was too aggressive to the human eye. In a dimly lit studio, it seemed almost bioluminescent. It was not slime green or lime green, but rather a slightly tainted version of a natural green tone. My friends hated looking at it. When I ran out of white primer, and started priming my canvas with this green, I knew it had changed my practice. It rejected the eye and seemed to hold a hazy cloud of pale green on the canvas. The resulting collection situates all my subjects in a field of glowing foam, each form emerging from a cloud of biomass particles. It became a metaphor for mutation and biological futurism. Additionally, the repeated saturation of green mocks traditional branding in green capitalism. Buyers are trained to believe green labeled products are beneficial both personally and ecologically.

The green appeared in all of my pieces, peaking through thin layers of oil paint. The paint tone was very appropriately sold as the shade Green Myth, which I eventually adopted as the name of this series. Ultimately, the myth in the Green Myth refers both to the historical development and proliferation of the hybrid entity, as well as the fictitious ideology that capital accumulation on Earth can continue into the future. This collection of work argues for a hybrid future, in which various social and sexual liberation fronts have to equate natural resources to their own bodies. The priority on future Earth is radical biodiversity.

The Green Myth

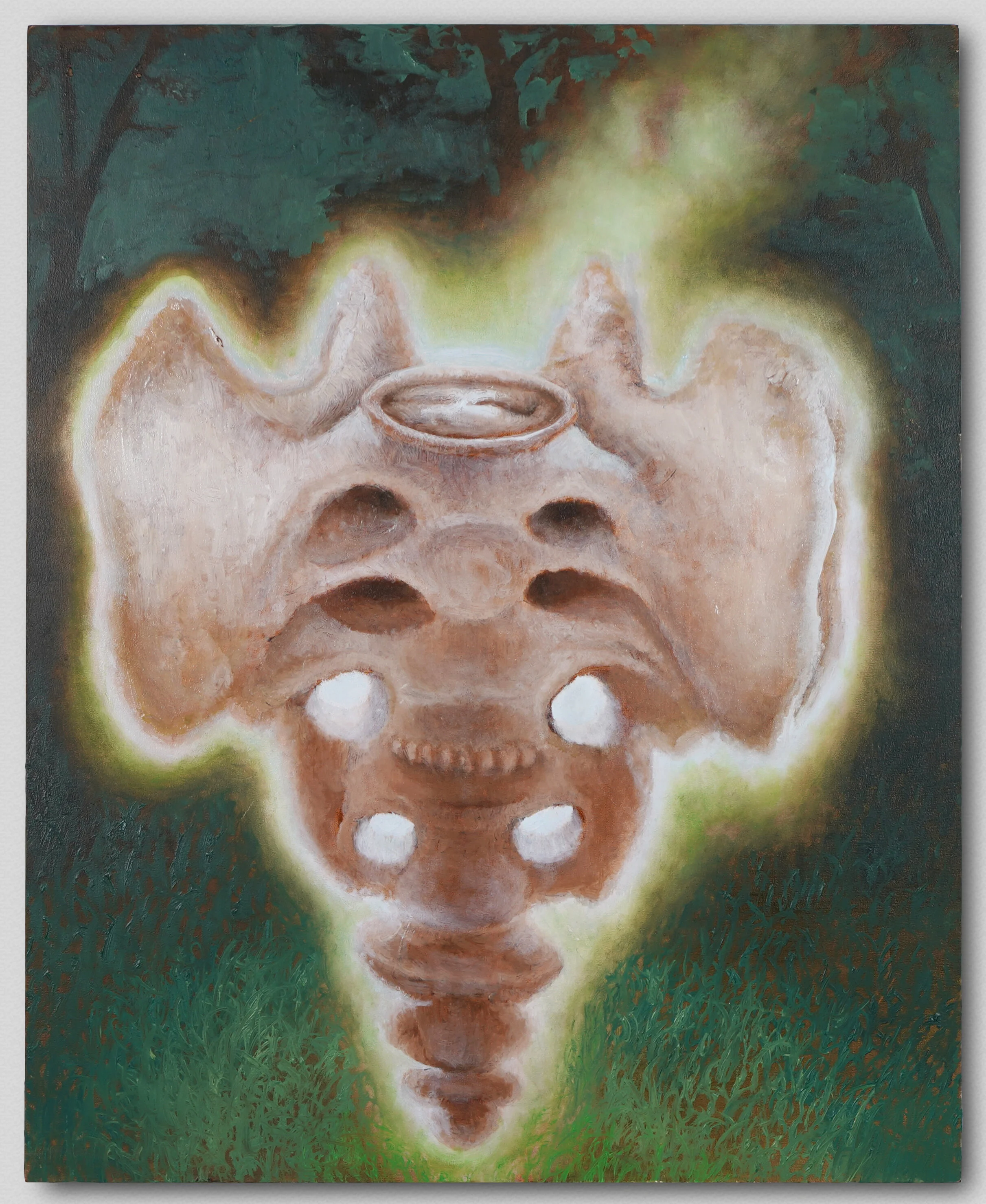

Fig. 1. A Great Potential for Mutation, 2019, oil on wood panel. 16” x 20”.

The earliest pieces I produced in this practice were a series of oil paintings on wood panel. I was slowly developing my method of paint mixing and surface treatment as practically linked to my conceptual endeavors. These paintings, produced in the fall of 2019, explored genetic mutation in reproduction and the potential end of human natality. After collecting anatomy books of the human skeletal system, I produced A Great Potential for Mutation, an oil painting on wood panel (fig. 1). The piece shows a human sacrum, the lowest bone on the spine attached to the pelvis, emanating a green flame in a dark forest scene. Positioned in nontraditional lighting, the bone suddenly resembles an animal in itself. Trying to visualize the unseen and seemingly paranormal forces of genetic mutation, this piece expanded on my interest in mutation as a rejection of continued humanist conquest.

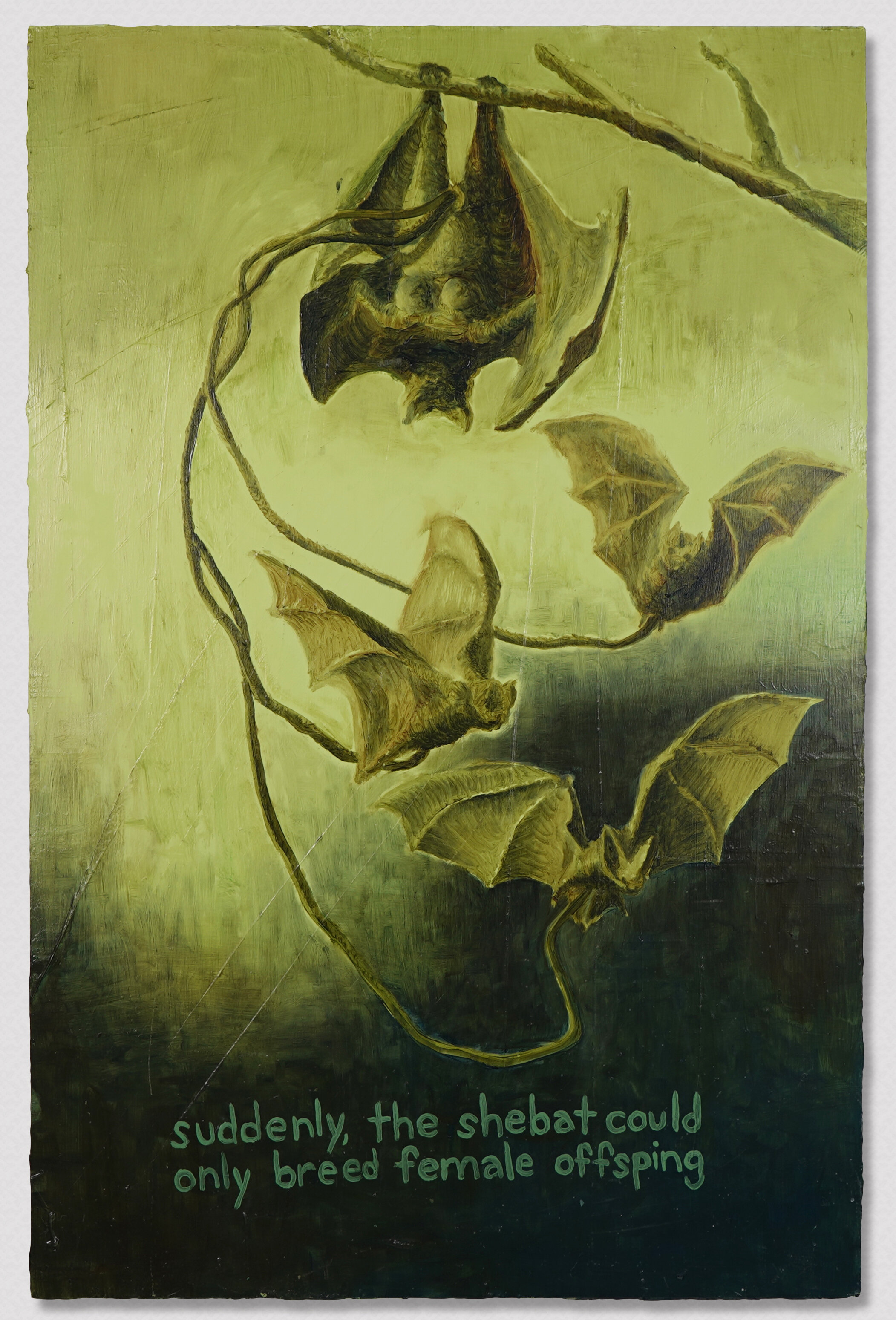

The piece Shebat touched on a similar idea (fig. 2). Painting monochromatically green on a found wood panel, I produced this piece in just two days. The sped-up mode of painting challenged my traditional image-rendering style and evoked the psychological urgency I was facing as the ecological disaster approached.

Fig. 2. Shebat, 2019, oil on wood panel. 24” x 36”.

The image shows a mother bat, the Shebat, giving birth to three other female bats. All three are connected to their umbilical cords, visually reflecting a family tree of genetic descendants. Across the bottom, I painted the declaration “Suddenly, the shebat could only breed female offspring.” The piece is in conversation with some ecofeminist thinkers who consider antinatalism, or the refusal of offspring, as a solution to resource shortages in the Anthropocene. Shebat is an allegory for potentials of human reproduction in the Anthropocene. At the time, I was fabricating a situation in which all babies born were suddenly female, and the human race could not replicate. In non-industrial nature, such an event would force a species into extinction.

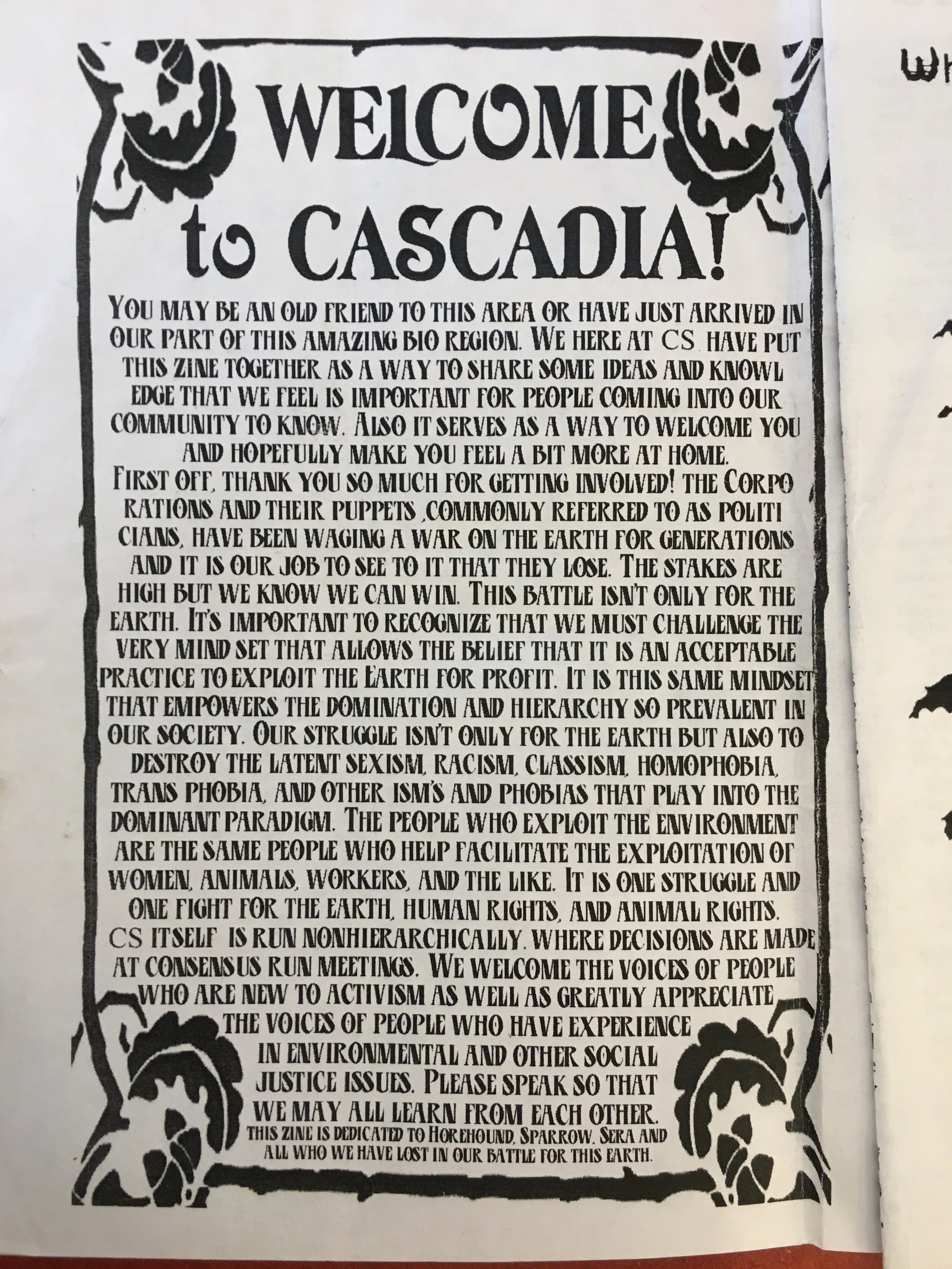

Inspired by political protest banners from the radical ecoactivist group Earth First!, in the winter of 2019 I moved away from wood panels and adopted oil painting on unstretched canvas. Finished pieces on unstretched canvas could be easily rolled and stored in more efficient ways then stretch canvas. Additionally, the unstretched pieces are grommeted in the corners for easy hanging as they would be if they were banners. This became my preferred material to paint on for the duration of my thesis practice.

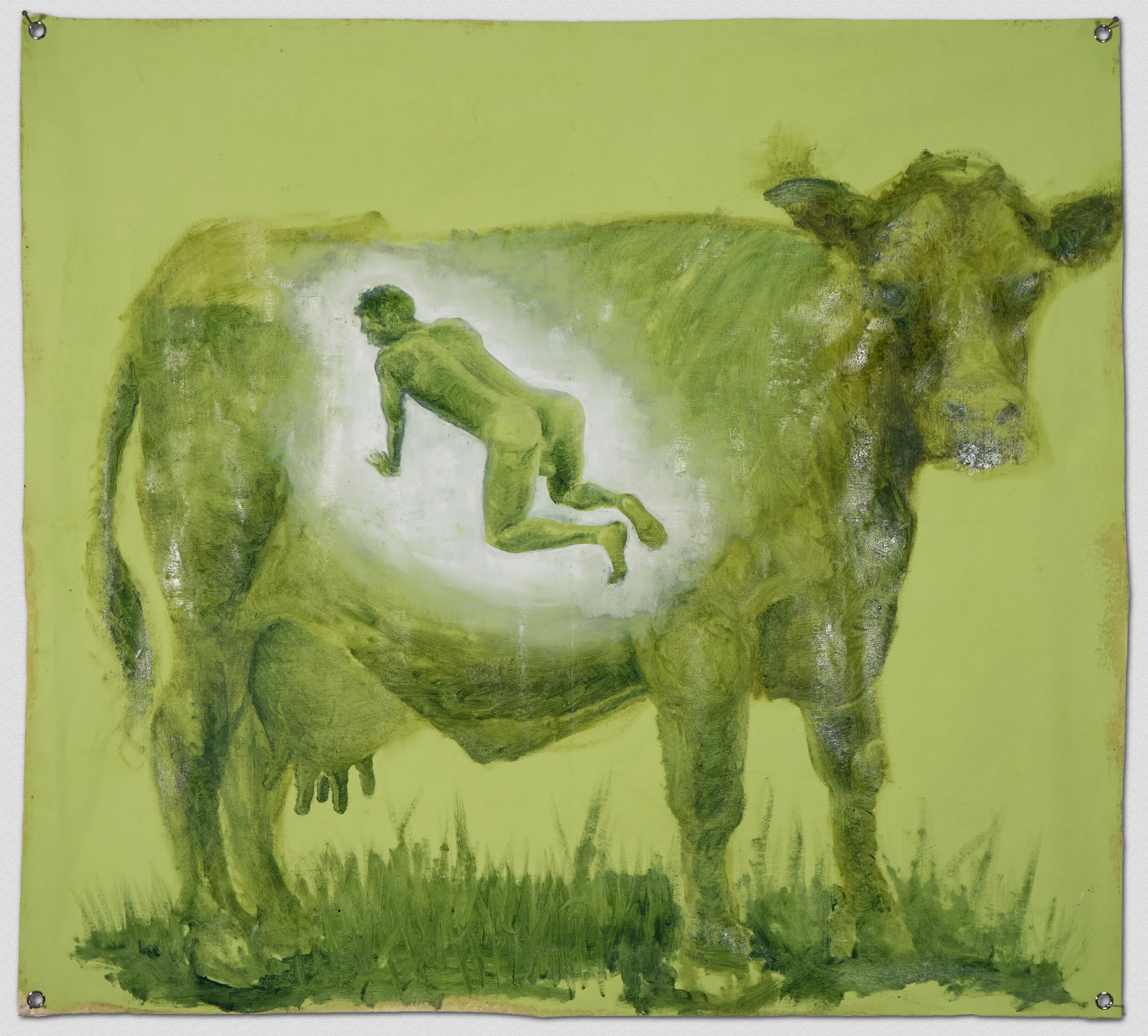

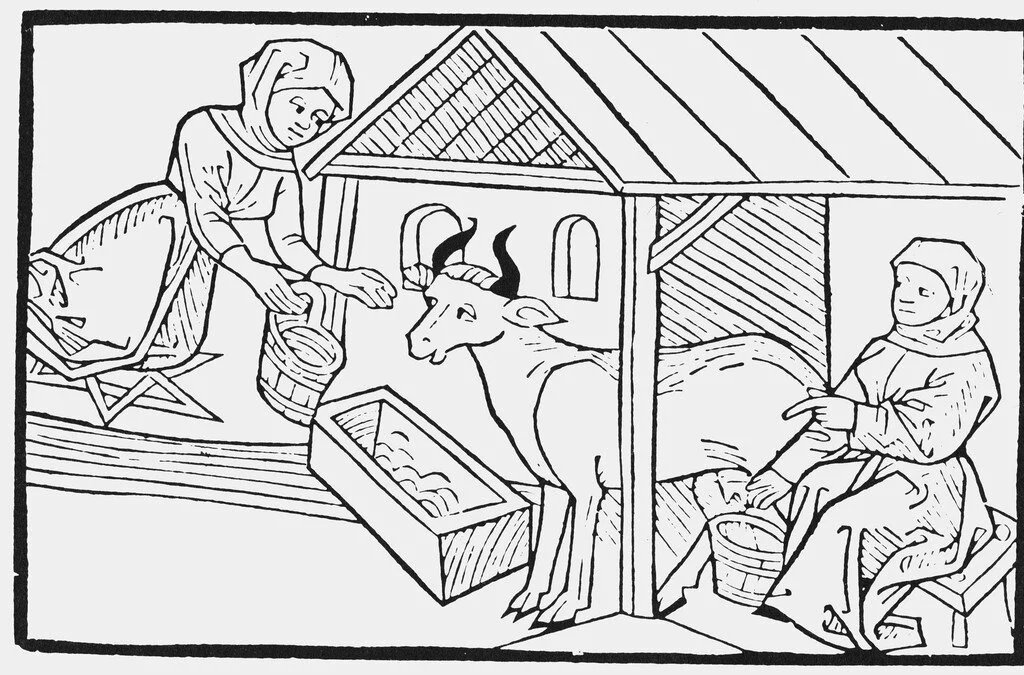

I initially made two banner paintings, a small series, grommeted and mounted on nails in my studio. Pigboy and Cowboy were the largest paintings I produced; their sizes resembled the scale of the animals they depicted. The mother pig in Pigboy is approximately the same size as a young sow. These pieces considered the reproductive politics related to farm animals and its potential relationship to human sexual liberation fronts. Pigboy shows a fertile pig with swollen teats mounted, empirically in profile, against the glowing Green Myth background (fig. 3). Floating in or above her midsection is a man sexually propositing the viewer. His feet, testicals, and anus exposed, he looks back at the audience with desire. Considering the contemporary discussions on the inherent privledges of heteronormative sexuality, the piece was meant to draw comparison between LGBTQ+ identity politics and sexual orientation of mass-inseminated livestock. There is a visual dialogue between the hanging shape of the man’s testicles and the hanging nipples of the sow. The matching piece, Cowboy depicts a similarly fertile female cow in profile, endowed with a hypersexualized man exposing his anus to the viewer (fig. 4). Unlike Pigboy, the cow is monochromatically in green; the expedited painting technique is similar to that in Shebat. The other function of these pieces was to poke fun at the idea of “queer art” that recently become extremely commercially sucessful in mass media. I see a similar ideology surrounding the effects of green capitalism. The humorous possibility of a cow identifying as queer, and thus mitigating the ability to have calves, challenges the actual social power and potential profit drive of contemporary queer branding.

Fig. 3. Pigboy, 2019, oil on unstretched canvas. 71” x 59”.

Fig. 4. Cowboy, 2019, oil on unstretched canvas. 41” x 45”.

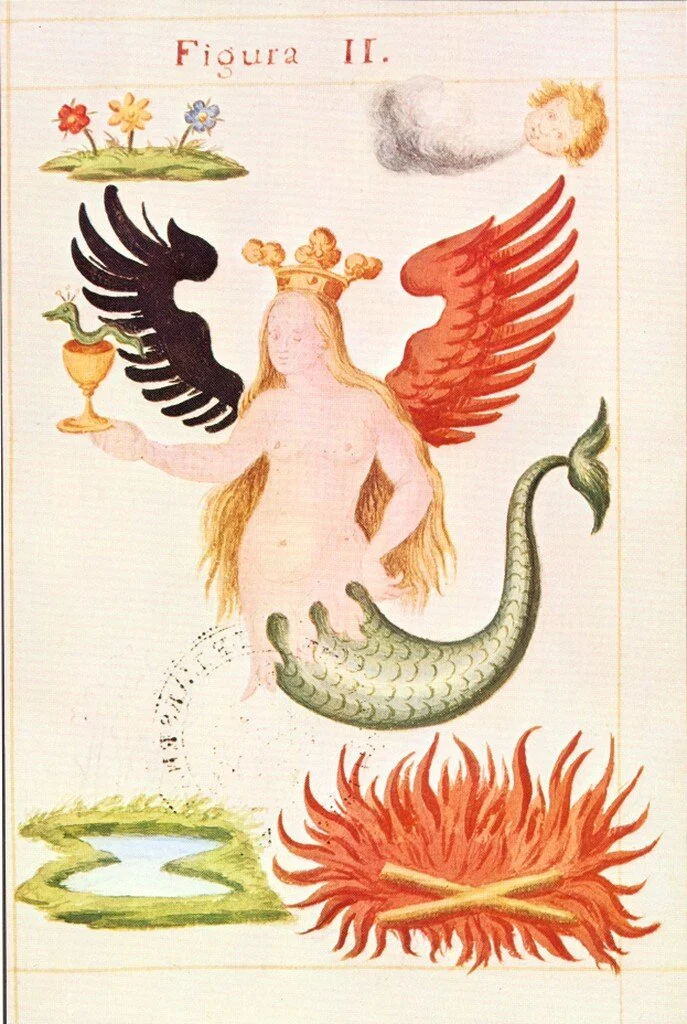

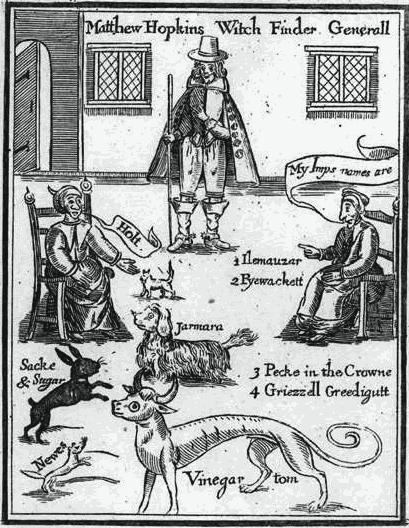

Around winter break I became invested in medieval imagery and art. Silvia Federici expanded on medieval European culture and its fear of witchcraft. A common theme in medieval times, the Apocalyptic paranoia surrounding witchcraft strangely reflected contemporary doomsday rhetoric about the ecosystem by mass media. Additionally, early zoologists in the 1300s began producing illuminated manuscripts of “exotic” animals previously unseen to the West. Colonial speculation and racial hierarchy produced the first illustrations of hybrid beasts.

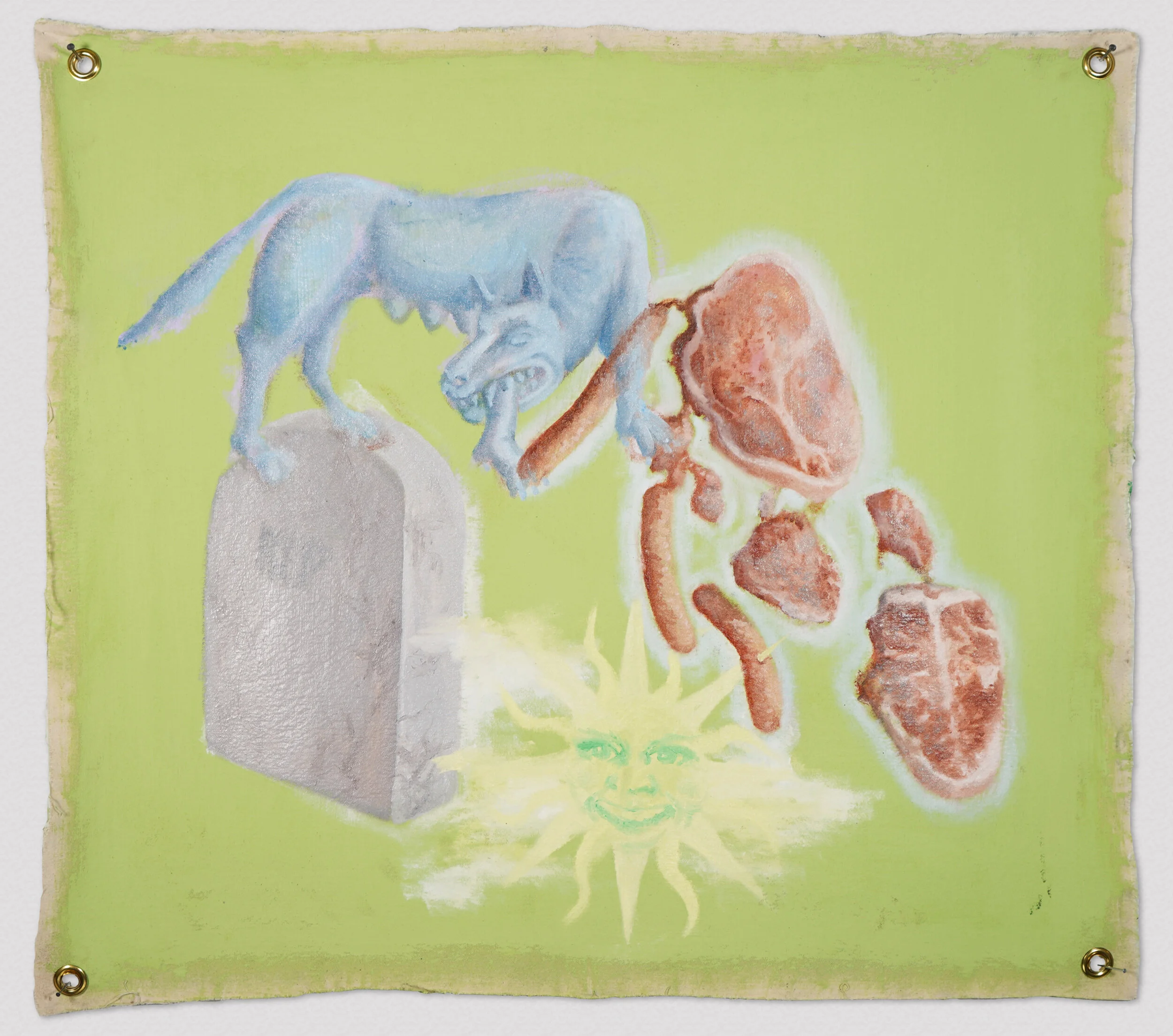

Fig. 5. Meat Cycle, 2019, oil on unstretched canvas. 31” x 36”.

Meat Cycle is an unstretched and grommeted canvas painting that utilizes the image of a shewolf (fig. 5). Set on the Green Myth background, the painting is presented as a cycle, similar to a biological cycle of organic material. The shewolf, teats swollen, bites her own leg amongsts a field of meat. Piercing the meats are the rays of a golden, smiling sun. In medieval art, the sun represented ultimate power and potential alchemical creation. Finishing the cycle is the gravestone, marking the death of traditional “meat” and the introduction of invention. Meat Cycle uses alchemical mutation, as feared in medieval culture for its ungodly connotation, as a device for criticizing the meat producing industry. I wanted to suggest a cycle in which meat, the substance we have on our own legs, could be transformed into something different to be consumed. Wanting to expand on the historical figure of the shewolf, I painted Shewolf on an unstretched canvas (fig. 6). Rendered in old master portraiture style, Shewolf portrays the mythical story of a wild female wolf protecting a human child. The shewolf's face resembles that of a stern human woman. Her teats are swollen and being suckled by the human child. Both figures emerge from a night time forest scene, the archetypal setting for the outcast human-beast. I wanted the painting to document interspecies kinship and the universal image of the mother. Shewolf is an inquiry into the potential for biodiversity, both in the history of Western culture and as a model for the future.

Fig. 6. Shewolf, 2019, oil on unstretched canvas. 47” x 27”.

The final piece I painted for this collection of work synthesized my year long research on biodiversity and the potentials of organic mutation. Entitled Seaspine, I used this unstretched canvas piece to opt out of human representation and focus on an abstracted biomass (fig. 7). Seaspine shows an underwater scene in which a central creature is expanding upwards into smaller, independent organisms. The original form, the genetic mother of the smaller units, resembles a human sacrum with attached iridescent fins and tentacles. Emerging from the sacrum are other marine animal body parts, including a notalisks shell and the snout of a seahorse. Reaching out from the top of the mother sacrum are two branches of blooming buds, resembling seaweed. Flowing out of the central form, like a school of fish, are tiny micro plankton and jellyfish. They are painted in gentle, almost transparents layers in contrast to the bone-like mother body. Encompassing the entire form is a saturated green light. Painting in gentle layers of glazing, I intend for the Seaspine to appear bioluminescent in the deep waters. This evolution of the human sacrum bone, the base of the spine, imagines a future in which interspecies evolution and biodiversity predicate the model of industrial expansion on Earth.

Fig. 7. Seaspine, 2019, oil on unstretched canvas. 49” x 41”.

Parallel to the paintings I was producing for this body of work, I became fascinated with the social mobility of pull tab posters. Intended to be displayed in partnership on the wall with the paintings, I produced a series of 20 pull tab posters. Inspired by actual pull tab posters I saw around my neighborhood in Queens, each poster imitates an actual memo that would be sent out to the New York City public. The poster’s subject matter adopts an unseen future reality in which genetic mutation and hybridism have taken force of the world ecology. Contrasting the utopic proposals as depicted in the paintings, I wanted the posters to project towards an ecological Apocalypse.

Fig. 8. Poster 4: Bondage, 2019, inkjet. 8.5” x 11”.

This poster parodies a personal ad of a dominatrix searching for sub (fig. 8). Implied in the description of the both participants is that they are both animals / hybrids of some form. Most notably, the writer is “octopedal” (like a spider) and the responder should be “quadrupedal” (like a pig).

Fig. 9. Poster 8, 2019, inkjet. 11” x 17”.

Poster 8 resembles a public service announcement about a new batch of fentanyl laced drugs one would see around New York City (fig. 9). Instead, the poster warns about a batch of ketamine turning users into horses. Ketamine being a popular party drug in New York queer clubs, the poster combines the future possibilities of biohazardous genetic mutation with ketamine’s original medical use as a horse tranquilizer.

Fig. 10. Poster 15, 2019, inkjet. 8.5” x 11”.

Poster 15 came from collecting images of lost animal notices I had seen on telephone poles in my neighborhood (fig. 10). To further reflect the diverse ethnic and class mobility of independently published pull tab posters, I had a friend translate Poster 15 into Mandarin. The text reports a missing pet rat, indicated in the picture to be a hybrid experiment, and offers a reward of $500 to anyone who could return the experimental rat back to its owner.

Fig. 11. Poster 9, 2019, inkjet. 8.5” x 11”.

Evoking the more traditional doomsday-prepper vocabulary, I produced Poster 9 as a call to a potential mate for the end of the world (fig. 11). The writer obviously expects to have to repopulate Earth; they ask anyone interested to be “extremely fertile.” Wanting the poster to pass at first glance as an actual advertisement, the title is a parody of the traditional moving ad poster, Man with a Van. Poster 9 is stark in design, given its manic nature and urgent call for a mate before the nuclear winter.

The pull posters are an efficient way to democratically distribute information to a larger group of viewers. Instead of objectively viewing a mounted artwork, the culture of pull tab posters integrates the viewer in the process. Like a bee transporting pollen to a different flower, the movement of ideas is more fluid if you can take a fraction of the painting off from the wall. This method was also inspired by the independently published and distributed pamphlets from radical ecoactivist groups like Earth First!

Methodologies

The initial state of research regarding this topic came from reading both contemporary and historical ecofeminist literature. Haraway is notably involved in digital publication, as much of her archival texts is available on various digital platforms. Much of what I found came in articles publish in feminist journals, as very few ecofeminist authors published entire books. Federici cites her recent publications regarding the history of witchcraft as being a response to Trumpism in America and the increasingly facistic governments structures around the world. Other literature included anthropological dissertations on mermaids, and the occasional museum review.

During the time of this research, I was taking a class on the history of political economics, and how neoliberalism structures contemporary Americansim. One of the speaking graduate students, Daniel Younessi, specifically talked about the term overpopulation and its “borderline fascist” contextual meaning. It was in this course that I wrote more about The Reserve Army of Labor and surplus labor. This shaped my own personal view of mutation and its traditional relationship to population. I knew my paintings would be informed by ecofeminist thinkers, while simultaneously criticizing their shortcomings.

In October I visited the Interference Archive in Red Hook, Brooklyn. Their collection of protest and independently published zines are “democratically organized”, meaning almost impossible to navigate. That said, I searched specifically through zines and independently published text for information about radical ecoactivism. One such discovery was paraphernalia from the leftist terrorist group (terra-ist as they note) Earth First!, distributed at a meeting in the 80s near where I was born in New Hampshire. Although much of the ecoactivist literature was clearly written by men, some texts explicitly emphasized the need for female centric organization in anarchist cells. Even more so, radical veganism zines repeatedly weaponized the hybrid as a symbol of exploitation in the current structure.

Following my own model of radical innovation in relationship to resources, I knew I wanted to adapt my traditional painting production to something ecologically sustainable. Additionally, my continuous exposure to my own painting materials in a small space would put my personal health at risk if the substances were toxic. Having been trained as a traditional Dutch style portrait painter by the artist Naruki Kukita in Brooklyn, I had a basic knowledge of mixing medium with pigments. The difference, in my case, is that I wanted all my materials to be non-toxic. Thus began a series of experiments with various natural pigments and mediums to mimic paint that was sold at the store. I developed my own natural Liquin medium; a mixture I still use now consisting of solvent-free gel medium, natural walnut oil, and non-toxic EcoGamsol. Over a period of testing various pigments and their hues in comparison to store bought paints, I found a steady set of colors I could regularly use. This includes my own version of the Zorn palette; a portraitist’s color range that only uses titanium white, yellow ochre, ivory black, and cadmium red. In my case, I specifically developed an additional range of green tones that were non-toxic. Starting at the base level of production where my money was being spent, I gained political agency as my practice reflected the innovation I was encouraging for others. It is my goal to produce my work consistently under my own ecocentric and ethical boundaries as a way to distill my painting skills and the theoretical meaning of my practice.

Research

I. Ecofeminism

The majority of the research I’m conducting is adapting radical ecological theory and activism, arising in the 70s and 80s, into a contemporary liberal context. It is my belief that linking the exploitation of sexual liberation to ecological sustainability and biodiversity acts more efficiently to counter capitalist systemic oppression. Radical ecological activism and thought came out of the late stages of wartime Second Wave Feminism and anti-nuclear protest culture. Most notably and important to my artistic practice are writers and activists associated with the Ecofeminist movement. Ecofeminism is defined as the linking between the domination of both nature and women. The mutual exploitation of women and nature can be seen in the cultural roles they play under patriarchal capitalism. Haraway calls for the hybridism of feminist ideology with animal-adopted evolution, as this is the only means of survival in capitalist ruins. In her book Staying with the Trouble, she strives towards the Chtulu, an omnipresent Gaia-like entity that combines all biology on Earth, as a model for society’s future. She states that both a feminine and ecological standard is the most efficient in all aspects of societal organization (this theory became the title and inspiration for Hito Steyerl’s Factory of the Sun). Haraway’s Chtulu vision is present in many works I produced, most notably the painting Seaspine (fig. 7). Working again with the anatomy book images of the sacrum, I wanted to visualize many smaller microorganisms emerging from a central skeletal form. Seaspine is both mythologically compiled (also a Gaia-like figure) and scientifically feasible. Inspired by Haraway’s writing, this biological form is cellularly complex but organized through feminist centralized ideology. The smaller organisms become as important as the larger entity.

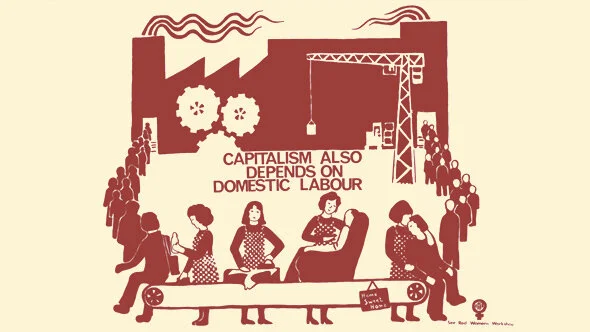

Feminist theologist Olga Consuelo Vélez Caro identifies that woman and nature are not one, as such an equation could mitigate the role of industrial violence performed by humans on the natural environment. That said, she encourages the shared liberation proposed by both activist fronts. To understand feminist equality and liberation is to also understand the need for decentralizing industrial consumption. A painting like Shebat directly compares the inherent need for reproductive bodies to bare offspring, and the need for continuous resource consumption in capitalism (fig. 2). The idea of a species of bats going extinct is scary to humans because it simulates the extinction of animals we rely on to survive. In post-capitalist society, the livestock animal is both a producer (of milk, of children, etc.) and a resource to be extracted. In Meat Cycle, the mother wolf biting her own leg shows a continuous string of infinite consumption and carnivorism (fig. 5). As the economic demand for meat rises in Western countries, industrial systems of artificial insemination can produce more highly fertile livestock. The theoretical recognition of animals as legitimate reproductive entities would equate their cultural standings to human mothers. In doing so, it is possible to recognize the shared goals of various ecological and feminist grassroot factions. The inherent goal of capital accumulation is categorization and class division.

II. Ecology and Rifting

Many argue it is a facet of contemporary free market ideology that we separate and further identify ourselves out of larger class groups. Slavoj Žižek describes this increasing drive for division and its relationship to ecology. He refers to the ecological separation between product and producer as a “rift”. The ecological rift, as Žižek describes, disrupts the understanding of labor as functioning within the nature system. Given the limited natural matter on Earth, the process of labor transforms one natural resource into a product to be sold. As market demand and surplus value extract more resources, there becomes a disillusion that this system operates within a larger ecological biome. Žižek points out that in the ideal socialist project, the lack of capitalistic systemic desire for surplus value would completely mitigate the rift between resource and finalized product; between laborer and economic agent. Relating back to class division, the rise of political agency in identity politics produces as many problems as it does solutions. The failure to see large scale oppression at the hands of capitalist accumulation, regardless of individual identity is produced by this same rifting effect. I relate this to how queer branding has overwhelmingly taken ahold of Western media. Adopting queer representation for marketing campaign ensures relatability and social awareness is linked to your business. In the paintings Cowboy and Pigboy, I compare the hypersexualized queer body to livestock (fig. 3)(fig. 4). Following Žižek’s logic, both are being extracted from their actual setting and packaged into something to be consumed on a larger scale. The result being a rift between the original cultural and the adopted buyer. Queer representation in digital media is negated by megacompanies continuing to financially suppress actual queer people and those in the lower economic class. Like the cow being artificially drained of her milk through her swollen teats, the man’s exposed testicles and anus are synthetically posed for the all-encompassing viewer. The queer body hides no secrets or agency, and ultimately becomes a logo. When selling identity as a kind of product for media success, the original exploitation of certain racial and sexual minorities is divorced from its finalized market value. Žižek states that the effect of rifting is apparent in both natural resource extract and social liberation fronts.

III. Reproduction and Population

Ecofeminist writers have continued to apply ecological activism to sexual politics, specifically cultural femmephobia, in a contemporary context. My introduction to this field of research came in May of 2019 when I read ecofeminist writer Silvia Federici’s book Caliban and The Witch, in which she discusses the history of witchcraft and its relationship to primitive accumulation. She highlights the importance of expanding on the traditional Marxian idea in order to appropriately draw similarities between systemic oppression of witches, non-reproductive bodies, workers, and other minority groups under capitalist accumulation. Primitive accumulation describes the earliest stages of capitalist development in Europe. This is understood as the first fundamental separation from workers and the goods they were producing. The divorce of product from producer and the capitalist ownership of these means of subsistence lead eventually to the capitalist class structure. According to Marx, primitive accumulation occurred in Europe for the first time around the 1500s. After the fall of Roman Imperial master-slave oriented society, the majority of Europeans lived under feudalism. This socioeconomic structure describes peasants living in huts under a lord, usually occupied in a castle. In return, peasants farmed and arranged communally. Their status as peasants placed no hierarchy in legality, and included women's freedom to work and run families. In addition, the farmer’s relationship to natural resource extraction was based entirely on sustenance and necessity. Crops were grown strictly to fulfill the food for survival, and all material was communally owned.

During the Middle Ages European populations were drastically declining and could not replace themselves. Warring between feudal states left many lords to lose their estates and disband their peasants. This coincides with the rise of political power gained by merchants, who would often repossess the abandoned states of lords and rule. Seeing the potential legal status of mercantilism, owners of land started privatizing. Marx would argue that the privatization of land began all capitalist

structural change. Barriers were established around private land to ensure crops could not be stolen (stealing, as a new idea). Farmers were expelled from their commons and forced to sell their farming labor in exchange for wages (Marx calls this ‘free labor’, meaning free agents in the market). Capitalism fundamentally requires exploitation, in which the goal is constant growth of profit. Although workers were now receiving a wage for their labor, the rate of exploitation and resource extraction for the market would limitlessly increase.

Caliban and the Witch fundamentally argued with Marx; Federici states that the earliest form of primitive accumulation should be considered the extortion of offspring from female bodies and the identification of the witch. Following the Black Plagues of the 1300s, populations in Europe were low enough that there was a cultural shift in the image of the female body. There appeared a new need for women to strictly reproduce, as her offspring would provide labor and protection. Women could no longer hold authority, have sexual liberation, or choose not to reproduce. Federici argued that it was the threat of women failing to reproduce that led to the witch trials in Europe. This capitalist accumulation directly mirrors that which is described by Marx during the extortion of common land. To classify the witch trials as the earliest capitalist-induced struggle would place feminist and ecofeminist emphasis on the historical and contemporary harm performed by capitalism.

IV. Reserve Army of Labor

Many Marxian scholars disagree with the ecofeminist description of the Anthropocene, labeling their thoughts as reactionary. The extraction of offspring from women and the continuous exploitation of Earth’s resources is accepted as true, but Marx would argue that the burden of overpopulation, and in fact the term overpopulation itself, places blame on lower class families in the capitalistic structure. In the post-capital world, the need for profit accumulation drives and growing class division has culturally established continuous reproduction; many contemporary Marxists would argue that in poverty-stricken neighborhoods often pregnancy is impossible to mitigate. Additionally, terms like the Anthropocene share the responsibility amongst all classes for the harm done to the ecosystem and the decline of natural resources. It can clearly be seen that it is actually the top class tier performing extreme violence against the ecosystem. Instead, this phenomenon and the embodiment of contemporary hybridism would be described by Marx’s theory of the Reserve Army of Labor.

The Reserve Army of Labor as a theoretical term in Das Kapital describes the surplus labor constantly present in the capitalist structure. This group is unemployed, and can not engage in selling labor on the free market. Marx argues that this group of unemployed, charity-reliant surplus population is both a prerequisite and product of capitalist accumulation. The RAL functionally drives workers to continue laboring and markets to grow, for fear they could be replaced by the constantly present surplus population. In terms of hybridism and the war on female bodies, this creates a paradox of cultural violence performed by the capitalist market. Hybrid “witches'' or other-bodies are a constant product of the capitalist market, yet often are blamed for the failure of resource distribution. In other words, as long as the capitalist market structure dominates public ideology, population grow will performatively be blamed on the lower class. The sentiment can be felt today, with the need for women to culturally have 2.5 children in a nuclear family.

V. Fear of Hybridism

Most dangerous to patriarchal dominance and capital growth was the witches failure to reproduce at the site of the human body. Federici drew similarities, culturally, between the image of the witch and that of the animal. Following primitive accumulation, to have a close relationship to nature or animals as anything other than resources was counterproductive. These events marked the beginning of a need to reject the animalistic body, for its failure to produce the laboring worker. Animals could not be sold as laborers to capital employers, so the association with the ‘natural’ posed a threat to industrial development. Primitive accumulation began the need to colonize both land and reproduction; the mythological and historical vitality of the hybrid female body suddenly challenged development. This meant a cultural separation between animals and humans. Thus was born the popular subject of beasiality in witchcraft, in which women fornicated with animals and nursed framiliars, or animal children. Beastiality was the enemy of Western development because the assumed offspring disrupted the human body at its basic level. More dangerous than stealing or murder was challenging the human image and anthropomorphic reproduction.

Many ecofeminist artists consistently identify this fear of the hybrid body as stemming from the original development of capitalism. Artists Genesis Breyer P-Orridge and Lady Jaye Breyer P-Orridge started an art project in the early 90s entitled Pandrogyne. Having been involved in a romantic and professional relationship as musicians, chaos magick experts, and performance artists, the Breyer P-Orridges pledged to sacrifice their bodies towards spiritual unification. Informed by the history of witchcraft and bodily transfiguration, the two started a series of plastic surgeries and hormonal treatments to have identical bodies. As their physical forms became similar, the resulting form, the pandrogyne, defied any binary idea of not only gender or sexuality but also identity all together. When Lady Jaye Breyer P-Orridge passed away, Genesis continued the pandrogyne transformation, stating that their ultimate pandrogyne form would be spiritually complete when they both drop their physical bodies. Most interesting to me was Genesis’ rejection, or, intentional satirization of contemporary identity politics and their relation to the human body. Although many queer theorists expand on the idea of the binary body as being limiting to gender identity, Genesis proposes a rejection of the human body entirely. Such “witchcraft” of the natural form, through elective surgery, proposes hybridism based on spiritual alignment with a larger entity. The posthuman body then becomes, for me, a site of radical art making. The intersection between sexual liberation in and the violent disruption of the human form was the embodied enemy of early surplus accumulation, and such cultural taboos continue on today.

VI. Posthuman Feminism

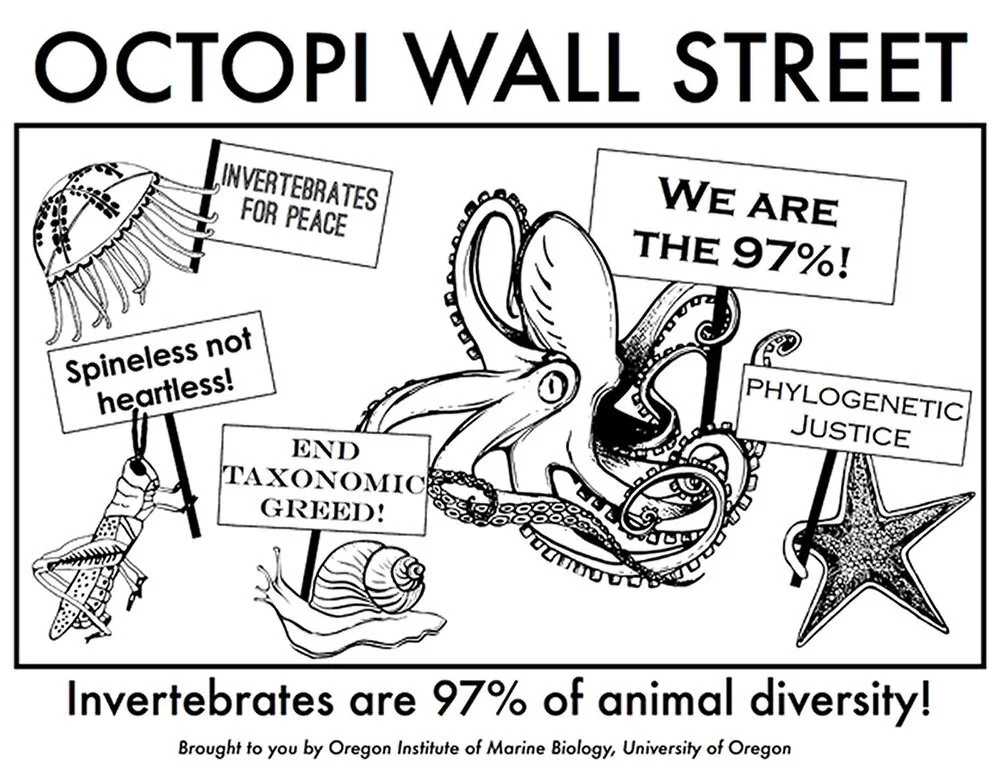

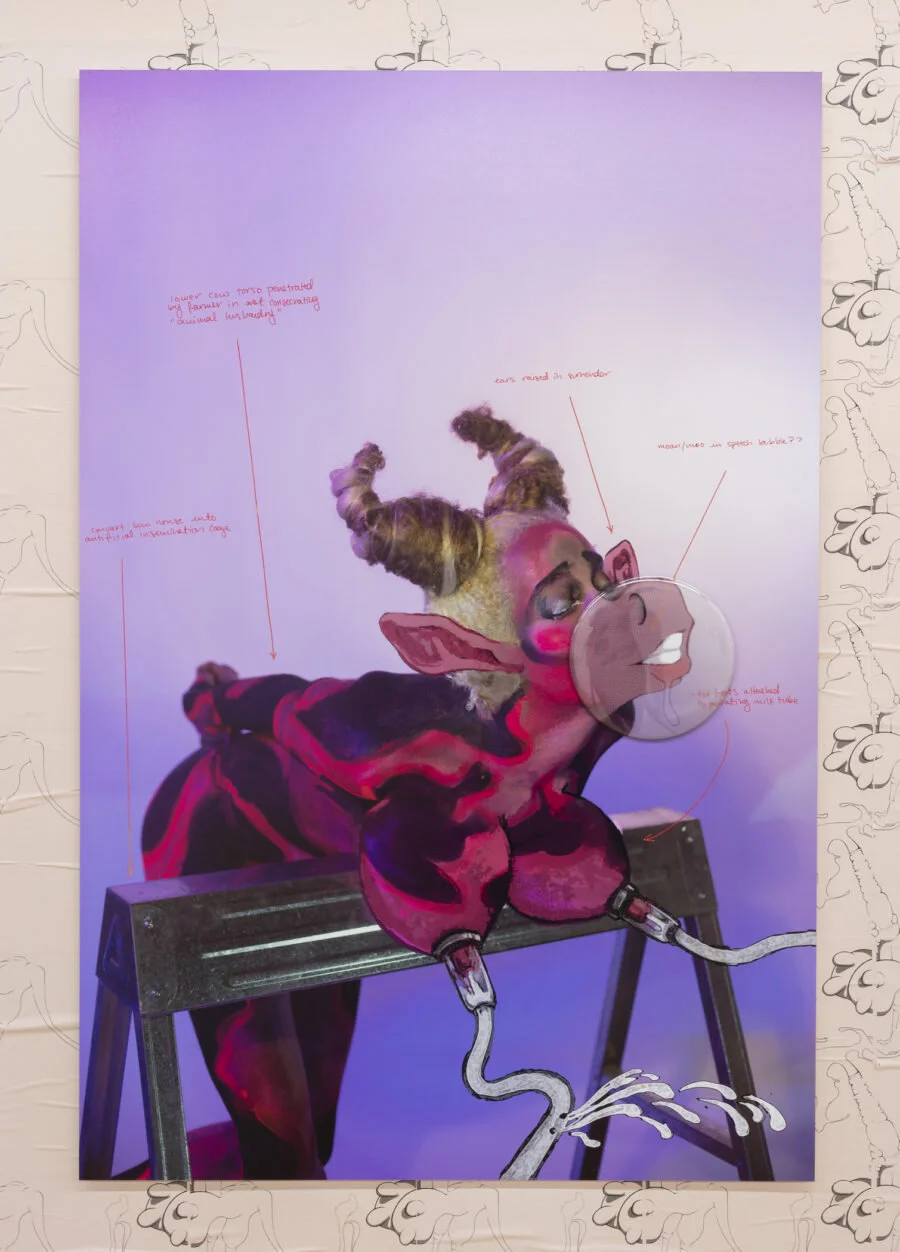

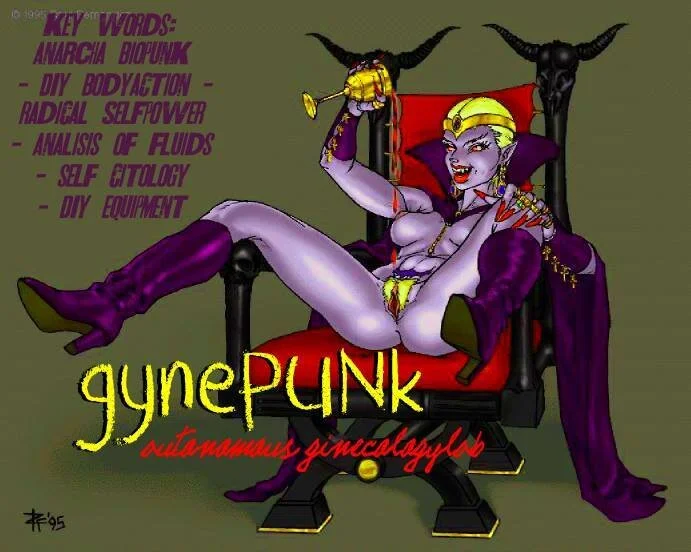

It seems to me that recent years of neoliberal media branding and right wing political mobilization has evoked a new generation of controversial ecological feminists utilizing hybridism. The hybrid body, be it slightly anthropomorphic or entirely microplankton, is the mascot of rebellion activism. Following her previous novel The Posthuman, Rosi Briadotti published her book Posthuman Knowledge in 2019. In both books, but more specifically the latter, Briadotti discusses the history of the humanist vision in the arts and its origins Western theology. She instead encourages subjectivity; in which the natural environment embodies not only nature but a God figure in itself. Her goal is to put into question the political obsession with navigating the biosphere through the humanist experience. My inquiry into the history of posthuman mythology is apparent in the painting Shewolf (fig. 6). The Roman story of a shewolf raising Romulus and Remus situates the proliferation of the human gene beyond anthropomorphic capability. After being nursed by the wolf, Romulus and Remus then become genetically posthuman; their offspring possessing inhuman cells. I would argue that the historic fear of “cellular paranoia” comes from the need to maintain the human form. The posthuman shewolf and her children, also called hybrids, represent a conceptual acknowledgement of the shared environment of all organisms in a given space. In the posthuman feminist projection, the body would be a site for largest systemic functionings. Briadotti talks about ‘second bodies’, referring to the new digital manifestation of the physical form. Such digital sphere, although seemingly opposing ecological success, allows for complex disruptions of the human-animal-ecosystem experience. Similar to Breyer P-Orridge, Briadotti’s posthuman feminism discusses cosmetic surgery as a way to disrupt the traditional body as a site for neoliberal identification. Political agency is immediately put into question once the human body no longer becomes human. The artist and poet Juliana Huxtable produced a series of printed images exploring the online fursona, or otherkin community as a kind of humanist decentralization. Huxtable gives legitimacy and sexual appeal to the hybrid body [she marks one poster with a pin reading ‘The Interspecies Liberation Front’] in an attempt to curate an environment for complex conversations regarding the animal industrial complex. As Huxtable’s avatars evolve from human to posthuman, the viewer considers all stages of the livestock animal from life and milk source, to meat and waste. Even in terms of compost, Briadotti and other posthuman feminists point out the laws regarding human bodies when they die; the natural decomposition of organic matter is a controversial topic. In the larger sense, feminist theorists are shifting the humanist experience to draw attention towards larger oppressive and unseen violences industrialization performs against Earth’s environment.

Conclusion

I. COVID-19

As I’m writing this analysis of my studio practice, I am 250 miles away from my studio. Being quarantined due to the outbreak of the COVID-19 coronavirus, I had to leave my paintings in the studio when I fled NYC. Ultimately, it was difficult to finish my practice because I was so removed from my physical studio. That said, I found that my research had prepared me for the end of the world. Since last May, I’ve been psychologically grooming myself for the absolute annihilation of the human race at the hands of some natural disaster. Additionally, it was my biggest fear that capitalist accumulation would supersede the need for human public safety. As my therapist told me over a Zoom chat, “You’ve been preparing yourself for the worst possible thing to happen, and it finally did.” But it was because of my practice, because of the words of Silvia Federicci and Greta Gaard, I knew that biology on Earth would evolve. Eventually, I found myself confident that we as a world would have to excogitate new ideas as the virus dies away, potentially for the better. In the past, the plague led to radical economic and social change in society (sometimes good, sometimes horrific). Although the human gene is certainly struggling to reproduce itself, non-human species are thriving in their ability to roam. I saw a video of a village in Wales in which the mountain goats had occupied the streets of a rural village because there was nobody outside to bother them. In addition, air pollution levels above China and Italy are at an all time low. To me, it proves fundamentally that the hierarchical relationship between Earth and humanity can change, either violently or intentionally. I really hate when people say these are ‘strange times’. Historically and biologically, this situation is not that strange. Humans have been contracting viruses from living amongst and consuming animals since the dawn of civilization. Influenza, Bubonic plague, Malaria, HIV/AIDS, ringworm, Ebola, and Lyme disease are all examples of zoonotic diseases and infections (meaning they are passed between animals and humans). To clarify, I’m not identifying that meat consumption is the enemy of humanity, although I think it certainly is detrimental to some extent. In fact, one could argue that meat consumption in a country like China is more ecologically sound because of a cultural emphasis on fresh produce. Most people in China who eat meat collect their meat from butchers and markets, in which there is a direct relationship between the producer and the product. Those living in extremely rural environments own their own means of production and food source. When there is no more livestock, there is no more meat to be consumed. Following my thesis research, I would argue that the public enemy of the human’s health is capitalist class structure. As the virus spread throughout the world, it was the lowest class of humans absorbing the death rates. Those without access to medical treatment, personal protective wear, food, or clean water were essentially sentenced to death by their economic status. Here in America, the lack of universal healthcare and early preventative measures due to individual frugality has cost thousands of people their lives; a large majority of those dead are black and brown people below the poverty line.

II. Looking Forward

The goal of my thesis project was to provide myself and my larger community of pears with hope for the future in terms of the ecological climate. It was comforting to know that long before I was born, groups like Earth First! and the ELA were serving jail time because of their desire to revolutionize human-Earth relations. This informed me that I was not the only one suffering from a general fear of the future. Moving my practice forward, I will continue to use my artistic medium to challenge human industrialism. Being back in New Hampshire, I’ve been able to reconsider my inherent consumerism in contrast to the natural environment. I spend lots of time in the woods, trying to draw spiritual and conceptual parallels between my art and my ecosystem. Given my lack of a studio, 100% of my paints have to be manually mixed from pigments and the non-toxic mediums I developed in New York. I plan on experimenting with painting in the woods, directly in relationship to natural resources. Without the need to transport myself to various places throughout the day, many of my daily activities like eating and reading can take place in the forest. In some sense, I feel I’ve hybridised my practice; obviously my art is highly connected to digital platforms and sharing, but I have the privilege to synthesize work directly from the landscape. The Green Myth demands innovation in biodiversity as a necessity for continued humanity on Earth. Additionally, my paintings and writings draw direct connections between the feminist and queer worldmaking as being predicated on ecological activism. Without an environment to exist within, all social and political achievements will be fruitless. Notable queer ecofeminist Greta Gaard often imagined a future in which various disinfranchised populations work together against capitalism. She stated in her book Toward a Queer Ecofeminism: “Rejecting colonization requires embracing [sexual liberation] in all its diversity and building coalitions for creating a democratic, ecological culture based on our shared liberation.”

Reference Images

Personal image, taken at Interference Archive in Brooklyn

Personal image, taken at Interference Archive in Brooklyn

Capitoline Shewolf

Digital collage by Nasim Najafi Aghdam

Digital collage by Nasim Najafi Aghdam

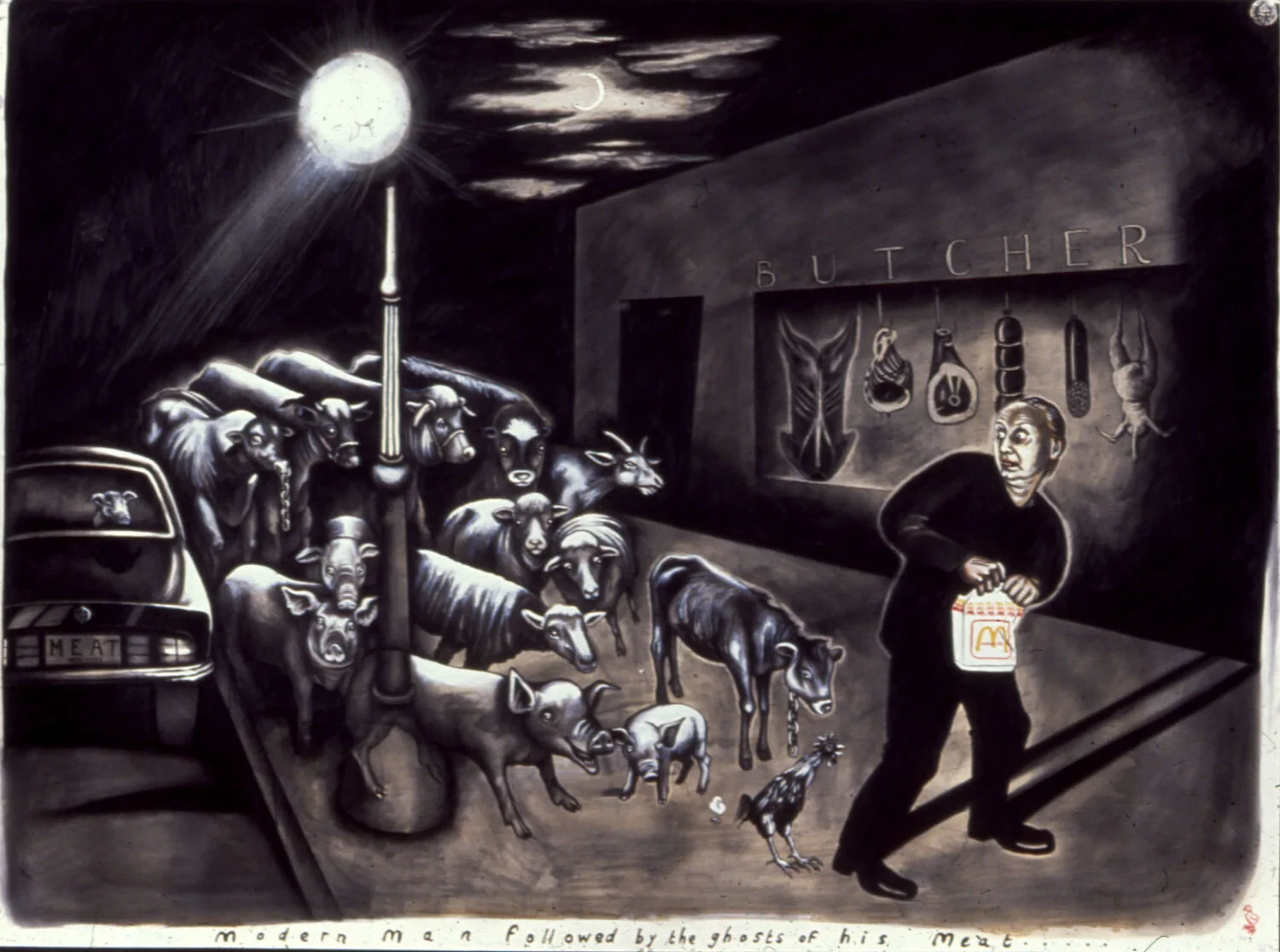

Modern Man Followed by the Ghosts of His Meat, Sue Coe. 1990.

Image by Donna Haraway

INTERFERTILITY INDUSTRIAL COMPLEX: SNATCH THE CALF BACK, 2019. Juliana Huxtable.

INTERFERTILITY INDUSTRIAL COMPLEX: SNATCH THE CALF BACK, 2019. Juliana Huxtable.

BibliographyBailey, Ronald. “We're All Gonna Die: Climate Change Apocalypse by 2050.” Reason. Reason, June 5, 2019. https://reason.com/2019/06/05/were-all-gonna-die-climate-change-apocalypse-by-2050/.Braidotti, Rosi. “A Theoretical Framework for the Critical Posthumanities.” Theory, Culture & Society 36, no. 6 (November 2019): 31–61.Caro, Olga Consuelo Vélez . 2005. “Ecofeminism: New Liberation Paths for Women and Nature”, Exchange Vol 44: Issue 1. Brill.Federici, Silvia. 2004. Caliban and the Witch. New York: Autonomedia.Gaard, Greta. (1997), Toward a Queer Ecofeminism. Hypatia, 12: 114-137.Gilbert, Krista Lauren. "The Mermaid Archetype," Pacifica Graduate Institute, 2007.Haraway, Donna. “Anthropocene, Capitalocene, Plantationocene, Chthulucene: Making Kin.” Environment Humanities, vol 6 (2015). pp. 159-165. http://environmentalhumanities.org/.Haraway, Donna. "A Cyborg Manifesto: Science, Technology, and Socialist-Feminism in the Late Twentieth Century." In Simians, Cyborgs and Women: The Reinvention of Nature. New York: Routledge, 1991, pp.149-181.Hielbroner, Robert. The Worldly Philosophers: The Lives, Times and Ideas of the Great Economic Thinkers. (New York, Touchstone, 1981). Kim, Hyunjee Nicole. “Hito Steyerl: Factory of the Sun.” this is tomorrow. this is tomorrow, August 14, 2017. http://thisistomorrow.info/articles/hito-steyerl-factory-of-the-sun.Love, Michael. “Juliana Huxtable's Bold New Work Shows Bodies as Alternate Species.” PAPER. PAPER, October 18, 2019. https://www.papermag.com/juliana-huxtable-infertility-2640989647.html.P-Orridge, Genesis. Thee Psychick Bible: Thee Apocryphal Scriptures Ov Genesis Breyer P-Orridge and Thee Third Mind Ov Thee Temple Ov Psychick Youth. Port Townsend, WA: Feral House, 2010.Tian, Qirui & Hilton, Denis & Becker, Maja. (2015). Confronting the meat paradox in different cultural contexts: Reactions among Chinese and French participants. Appetite. 96. 10.1016/j.appet.2015.09.009.Thomas, Brian. Vital Function Found for Whale 'Leg' Bones, 2014, Institute for Creative Research. https://www.icr.org/article/vital-function-found-for-whale-leg.“What Do We Know about the Top 20 Global Polluters?” The Guardian. Guardian News and Media, October 9, 2019.Žižek, Slavoj. “Where is the Rift? Marx, Lacan, Capitalism, and Ecology” The Philosophical Salon. Los Angeles Review of Books, January 20, 2020. https://thephilosophicalsalon.com/where-is-the-rift-marx-lacan-capitalism-and-ecology/